This week’s chart explores the contribution of the trade balance in the balance of payments to the evolution of New Zealand’s high external debt ratio.

The issue is significant because of the popular myth that the high net external debt ratio today results from a chronic inability of New Zealanders to save enough, for example, in the last two decades. This, it is thought, is the cause of the chronic balance of payments current account deficits since 1974. In reality, what was driving the deficits between around 1990 and 2004 was the cost of serving the net external debt built up by 1990.

This savings myth is bolstering the drive to force or subsidise today’s working age New Zealanders to save more.

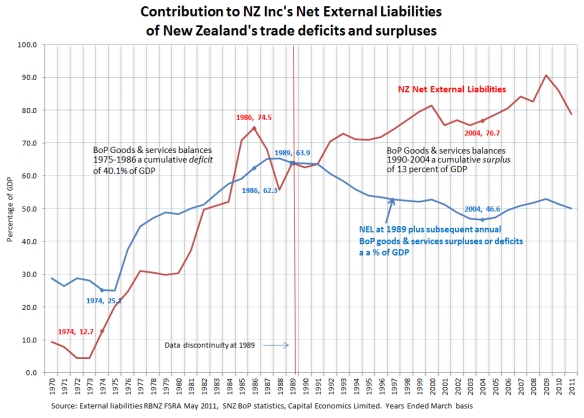

The red line on the chart shows New Zealand’s net external liabilities as a percentage of GDP. It uses two time series published by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in its May 2011 Financial Stability Report. The first series, from 1972 to 1989 is an unofficial series. The second series, from 1989 to 2011, is the official time series. (Statistics New Zealand has since published revised statistics, but the RBNZ’s second series suffices for the purposes of this analysis.)

The first point to observe about the red line is that its level today is largely a legacy of the events that caused the 1984 foreign exchange crisis. The ratio peaked at 74.5 percent in 1986 and is not vastly higher today.

The blue line in the chart plots how the net external debt to GDP ratio would have moved forward and backward through time from 1989 if the only factor operating had been the surplus or deficit in the trade balance of the balance of payments as a percentage of GDP in each successive year.

Focus first on the concurrent sharp rise in both the red and blue lines from the early 1970s to the late 1980s. The unofficial estimate of the net external debt rose from 12.7 percent of GDP in 1974 to 63.9 percent in 1989, a rise of 51.2 percentage points of GDP. That’s a massive contribution to today’s figure of around 80 percent.

The blue line shows the cumulative contribution to this rise of the large trade deficits (imports greater than exports) that occurred between 1975 and 1986. Summing the annual trade deficits as a percentage of GDP between 1975 and 1986 gives a cumulative deficit of 40.1 percent of GDP. That’s a big number too.

It follows that the large trade deficits that followed New Zealand’s failure to adjust rapidly and flexibly to the 1973-74 oil shock may explain roughly half of the net external debt of 80 percent of GDP that is causing such widespread angst today. This was not a savings deficiency story (see below). Instead the proximate reasons were the failure of the heavily controlled economy to respond adequately to the oil price shocks and the heavy overseas borrowing during this period to bolster the exchange rate and fund the large fiscal deficits.

Next, focus on the post-1989 period in the chart. The drop in the blue line occurs because, contrary to much popular belief, New Zealand ran surpluses overall in the balance of trade between 1990 and 2004.

It was only after 2004, when big government spending increases commenced, that the balance of trade returned to deficits, causing the blue line to lift slightly. The divergence between the blue and red lines after 1989 shows that the rise in net external liabilities from 63.9 percent of GDP in 1989 to 76.7 percent in 2004 was not a ‘spending beyond our means’ story. To the contrary, domestic (consumption and investment) spending was lower than domestic production/income on average during this period.

Another reason for not unduly focusing on the savings aspect is that it is perfectly sensible to borrow overseas to fund some portion of domestic investment as long as the returns from that investment adequately cover the cost of borrowing, taking risk into account.

Savings rates are one thing, competitiveness is another. New Zealand’s exposed industries can lose competitiveness at any given savings ratio simply because of adverse international or domestic events, such as the big rise in government spending that occurred after 2004.

The loss of competitiveness after 2004 is a real concern from an economic management perspective, given the historically favourable export prices relative to import prices during this period.

Those who insist on portraying today’s high net external debt ratio as a savings deficiency story should be aware that New Zealand’s average gross national savings ratio was actually higher, at 19.6 percent of GDP, between 1972 and 1987 than it was between 1988 and 2004 when it averaged 17.2 percent of GDP.

Not shown in the chart is the second major factor affecting the ratio of net external liabilities to GDP. This is the difference between the earnings rate payable on the net debt and the growth in GDP. The former increases the numerator, the latter the denominator. The rise in the red line in the chart after 1989, in conjunction with the fall in the blue line, suggests that the net earnings rate has exceeded the growth rate in GDP during this period.

Since New Zealand is too small to affect investors’ required return on capital, those who are concerned to see the ratio fall should be focusing on raising the rate of growth in GDP. This needs to be done in conjunction with restoring competitiveness in the traded goods sector in order to stop the blue line from lifting unduly.

In summary, New Zealand’s high net external liabilities are largely a legacy of New Zealand’s pre-1984 ‘Polish shipyard’ economy (with apologies to post 1970s Poland). They reflect past economic mismanagement and adverse oil price shocks, rather than any sudden change in national savings rates. The reforms of the 1984-1991, including the move to a floating exchange rate, a disciplined monetary policy, and the progressive elimination of fiscal deficits, put an end to the chronic trade deficits of the earlier period. Unhappily, the 2004-2008 loss of competitiveness and government spending discipline does not even have an adverse terms of trade excuse.

It could be worse than futile to try to penalise the current generation of workers for pre-1984 poor economic management by interfering with their consumption/savings decisions. The focus instead should be on raising income growth, in part by raising external competitiveness. After all, given the income gap with Australia and the number of New Zealanders voting with their feet, many would argue that raising the growth rate should be the focus even if the net external debt ratio were half what it is today.

A related point for those preoccupied with savings, as distinct from a higher savings ratio, is that higher growth means higher incomes and likely higher savings and consumption.

Still blogging to the end. This was a man who really cared about New Zealand and wanted to see it prosper rather than stagnate. RIP.

RIP Roger. Your contribution will last beyond your life. A man whose contribution and desire for a better New Zealand was lost on those who sought to take sides.

I always loved listening to you in the mornings when you were on ZB. You always made sense and now we are poorer for your leaving. RIP.

RIP. My condolences to your family.

Roger, I’ve personally known you since 1992. Thanks for your support encouragement and sometimes dissenting views. Many are saying rest in peace, I prefer to think that matter and energy can’t be destroyed.

See you on the flip side.

Cheers

Chris Simpson

A fitting tribute to Roger is that the entire post above – his whole blog – can be summarized four words: Socialism Wrecked New Zealand

Socialist governments in the 70’s gave us massive deficits and a huge bludger culture: Ruth Richardson (not Douglas) did her best, but then Labour took us to where we are now: even worse off than in 1991

The true memorial to Roger Kerr is a simple one Party Vote ACT: Enact the 2025 Taskforce report in full in a single term; end all forms of welfare for ever in NZ

When 1000 people apply for a supermarket job, you know that there is a problem.

Those who fail to learn from history, will repeat it. Can you imagine being dragged to a poor house because you can’t pay a bill? The 19th Century was hard on the poor. And there was no way to better yourself.

There is some welfare that we should retain, free education, free access to information, access to food, shelter and hope. And if we don’t, then we should ensure that all workers earn enough to ensure they can have access to these things. You can’t have it both ways, either business pays the true cost of wages, or they pay taxes to support the people that can’t survive.

The only way we can get rid of welfare is to ensure that wages are more than adequate to enable a person to look after their family.

It will be strange without Roger Kerr, I might not have fully agreed with him, but I always respected his intelligence and logic.

When 1000 people apply for a supermarket job, you know that there is a problem.

Sure there is a problem: heavy-handed laws, unions, and benefits are keeping the wages for supermarket jobs far higher than they should be. Once they are removed, this will no longer be a problem.

The only way to get rid of welfare is to do the one thing every high-value, high-worth Kiwi – like Roger – knows needs to happen: stop paying welfare.

Whether it’s the DPB or the WFF or the hospital bills or the super or the school fees or the GP – just stop the lot. Do that and you’ve got rid of welfare. We could do it tomorrow if John Key had a tenth of the courage of Roger Kerr or Ruth Richardson!

Fare thee well, Roger. You’ve done great service, and will be missed by those who know what you’ve contributed. I’m sad that I shall no longer have the pleasing distraction of reading your blog each day.