The Business Roundtable published a review of a new biography of Adam Smith as one of our regular Perspectives yesterday. Adam Smith is a man much revered by the Mont Pelerin Society and his enduring ideas and their striking relevance to the problems facing many economies today have been widely discussed at the Society’s general meeting in Sydney this week. Yet little is known about the man himself, as Jeffrey Collins explains in the Wall St Journal review:

Having dined with Adam Smith on a number of occasions, Samuel Johnson once described him “as dull a dog as he had ever met with.” Smith’s biographers might be inclined to agree. The most celebrated political economist in history led a remarkably quiet life. Born in the sleepy Scottish port of Kirkcaldy in 1723, he was raised by his widowed mother and lived with her for much of his life. He studied at the University of Glasgow (which he loved) and at Oxford (which he loathed). Only once in his life did he travel outside of Britain. He wrote few letters and burned his personal papers shortly before his death in 1790. Even his appearance is a mystery. The only contemporary likenesses of him are two small, carved medallions. We know Adam Smith as we know the ancients, in colorless stone.

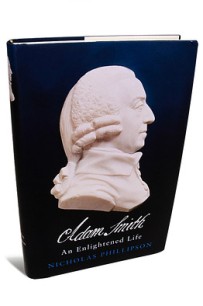

It is a measure of Nicholas Phillipson’s gifts as a writer that he has, from this unpromising material, produced a fascinating book. Mr. Phillipson is the world’s leading historian of the Scottish Enlightenment. His “Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life” animates Smith’s prosaic personal history with an account of the eventful times through which he lived and the revolutionary ideas that inspired him. Adam Smith finally has the biography that he deserves, and it could not be more timely.

In shedding light on Adam Smith’s character Collins explains that his philosophical ambitions were much broader than the “Wealth of Nations” might suggest, and ranged over politics, law, ethics and aesthetics.

Inspired by his friend, the skeptic David Hume, Smith swept aside all timeless or divine notions of moral and political order. In his view, society emerged from the historical experience of a needy species driven to create conditions in which property, affection and opinions alike could be stably exchanged. Manners and morals, like goods, thus had an “economy.” The material and moral economies were, indeed, linked, in that a rising material prosperity helped to encourage civility and taste. Mr. Phillipson reconstructs Smith’s intricate system with erudition and imagination, often from student notes of Smith’s long-lost lectures, which he had delivered in both Glasgow and Edinburgh.

As many of today’s debt-laden countries search for new ways to reignite economic growth, it seems a read of Mr Phillipson’s “Wealth of Ideas” would be well worth while.

Smith’s was a complex legacy, and in reading about it one is struck by its uncanny relevance. When the “Wealth of Nations” appeared, Britain staggered under massive war spending and a colossal national debt. Bad loans blighted banks across the country. Several had collapsed, leaving their investors ruined. Gold bugs abounded. In the face of international competition, well-connected manufacturing interests clamored for protective tariffs. The times called for Adam Smith, and his theories worked to stabilize and liberate the British economy as it entered the industrial age. If we need a reminder of his achievements, and of late it appears that we may, Mr. Phillipson has given us a superlative one.